Linear A & Linear B

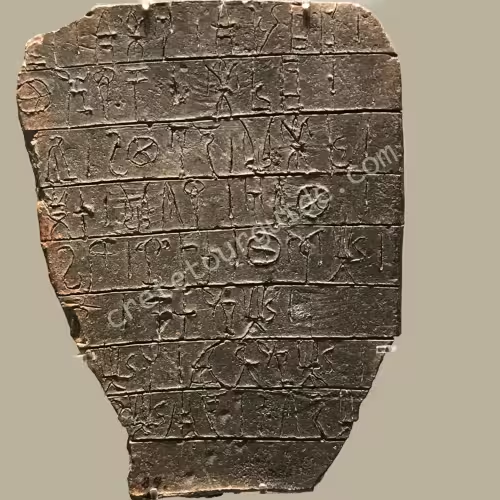

The Minoan Civilisation is considered prehistoric, as the term prehistoric generally refers to periods before the advent of written historical records. While Crete does possess examples of written records in two scripts —Linear A and Linear B— these do not fully transition the era into recorded history. The term linear refers to the method of inscribing lines into wet clay tablets. Linear A tablets were first unearthed in 1900 by Sir Arthur Evans, the British archaeologist who excavated Knossos.

Both Linear A and Linear B scripts were used during the 2nd millennium BCE. Despite their existence, the period is still classified as prehistoric, since Linear A remains undeciphered, and Linear B, though deciphered, contains texts that are administrative rather than historical. Most Linear B inscriptions consist of lists related to ritual offerings, inventories of goods, military equipment, and other records of an economic nature.

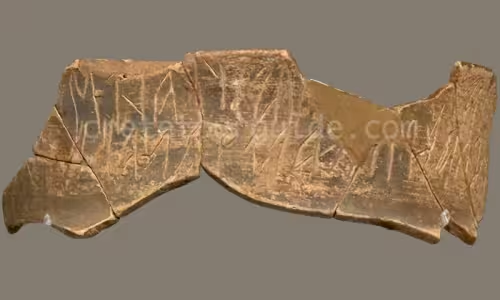

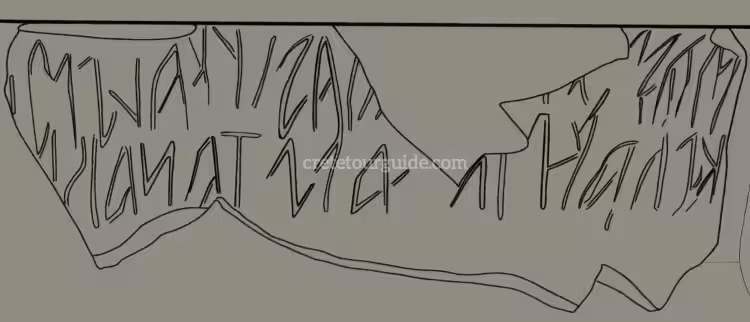

The earliest form of writing in Crete is the so-called hieroglyphic Minoan script, which also remains undeciphered. The relationship between hieroglyphic Minoan and Linear A is uncertain, though the hieroglyphic script likely predates Linear A. Linear A, which emerged shortly after the hieroglyphic script, is characterized by its neat structure and is almost always written from left to right. This script was in use from approximately 1850 BCE to 1400 BCE and is thought to represent a language of Minoan Crete. However, examples of Linear A have also been found on some Aegean islands. Key Minoan sites where Linear A inscriptions have been discovered include Haghia Triadha, Khania, Knossos, Phaistos, and Malia. Linear B, on the other hand, appears not only in Cretan sites like Knossos and Khania but also in mainland Greek locations such as Pylos, Mycenae, Tiryns, and Thebes.

Linear A is a syllabic script with over 90 characters, many of which are identical to those in Linear B. The latter was deciphered in 1952 by Michael Ventris, who determined that Linear B represents the earliest known Greek dialect, Mycenaean Greek. Linear B is essentially an adapted version of Linear A, with its signs corresponding phonetically to syllables. Scholars have attempted to apply the phonetic values of Linear B to Linear A texts, enabling them to “read” the latter, but the underlying language of Linear A remains unidentified. The books of Peter Van Soesbergen are absolutely worth reading and can be found here.

The Mycenaean Greeks adapted Linear A into Linear B to represent their Greek dialect. Linear B was in use from approximately 1400 BCE to 1200 BCE and is invaluable for linguistics, as it provides insights into Mycenaean Greek. Elements of this archaic dialect are discernible in the language of Homer, preserved through a long tradition of oral epic poetry.

Additionally, inscriptions in the Eteocretan language, written in Greek letters, have been discovered in eastern Crete. The term Eteocretan translates to “true Cretan” in ancient Greek. These inscriptions, dating from the late 7th or early 6th century BCE to the 3rd century BCE, are too few in number to yield substantial information about the language. The connection between Eteocretan and Linear A remains unclear.

In conclusion, while the Minoan writing systems offer fascinating glimpses into the civilisation, significant mysteries remain, particularly regarding Linear A and the language spoken by the Minoan people. These undeciphered texts continue to pose challenges for researchers and serve as a testament to the complexity of the ancient Minoan world.